Exposed

Why are we propping up animal ag?

Blog written by Victoria Smith, volunteer blog writer

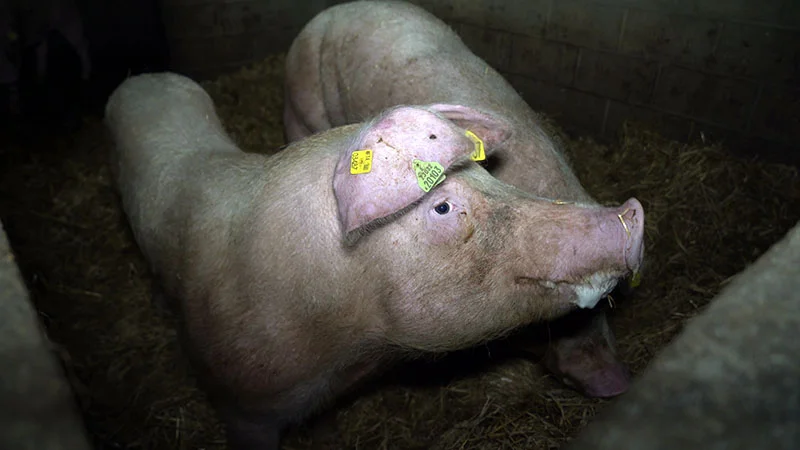

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which heavily influences the entire food system of the European Union (EU) via subsidies, was found by a study to massively favour the production of animal-based foods. The study, published in Nature Food last year, found that a massive 82% of the programme’s subsidies are allocated to animal farming; 38% directly, and 44% towards animal feed.

These findings are questionable, when a visit to CAP's page on the EU website describes, within the first few lines, how this partnership ‘between Europe and its farmers’ exists not only to support the latter in ‘ensuring a stable supply of affordable food’, but also aims to ‘help tackle climate change and the sustainable management of natural resources’.

If this is the case, one could be forgiven for being slightly confused that billions of Euros of the EU budget is being allocated to the products that account for 84% of the Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of European food production. A 2022 report claimed that between 2023-2027, 40% of the CAP budget would ‘go to environmentally respectful farming’, however if over 80% is currently going to animal agriculture, there seems either to be a mathematical contradiction, or a gross misunderstanding of what ‘environmentally respectful’ means.

A brief recap of how animal agriculture doesn’t respect nature…

- Globally, animal products use ‘~83% of…farmland and contribute 56 to 58% of food’s different emissions’ (Poore & Nemecek 2018).

- The meat industry is the single biggest cause of deforestation worldwide.

- Animal agriculture both uses a vast amount of water, and also pollutes local water bodies with its waste. A 2024 report by the Soil Association found that if the government doesn't put a stop to new chicken farms, rivers in at least 7 different UK counties are at risk of becoming dead zones.

- It causes desertification.

- It is a leading cause of biodiversity loss.

- Animal ag causes air pollution. A 2021 study conducted in the United States found that almost 13,000 deaths per year could be attributed to air pollution from animal agriculture. The breakdown of slurry creates ammonia emissions, which can cause serious respiratory issues.

Animal agriculture is not 'environmentally respectful'

So, ironically, whilst the 2022 CAP report boasts of its success in ensuring ongoing food security across Europe throughout the crises of COVID-19 & the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in the continued funding of animal agriculture they’re directly contributing to an industry that poses an even greater threat to our food security. Based on a global increase in the consumption of animal products, there are predictions of a potential 80% rise in meat-production Greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, with scholars warning that ‘the impacts of the livestock sector alone may bring irreversible environmental changes regardless of any technological methods of addressing climate change.’ And these environmental changes will result in extended heatwaves, droughts and flooding that in turn mean crop failures and a potential breakdown of food supplies.

Business as usual, however, is unsurprising. When we think of the farmers who bring food to our dinner tables, we picture family-run farms in rolling countryside, however the meat industry is a global powerhouse, with an estimated value of $1,460 billion in 2024. Between ‘2015 and 2020, global meat and dairy companies received over $478 billion in backing by over 2,500 investment firms, banks, and pension funds headquartered around the globe’, according to a report by Foodrise. And with this amount of money, comes a lot of power and a lot of influence.

Animal farming is destroying the planet

In 2023, a draft of an upcoming assessment by The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was leaked, which included the advice that ‘plant-based diets can reduce GHG emissions by up to 50% compared to the average emission intensive Western diet’. When the report was published, this text was missing, and it came to light that this change was due to lobbying from representatives of the meat industry.

Corporate influence goes a long way in explaining policy choices that not only fail to place restrictions on animal agriculture, but positively fund it. This study suggests a co-dependency between governments and the meat production and processing industries, arguing that the latter are major contributors to rural livelihoods and to the economies of many countries, and thus involve 'a number of organised interest groups' who use 'their power to maintain the status quo and undermine efforts at reduction’.

Yet, despite the huge numbers previously mentioned, animal agriculture doesn’t actually seem to be a very economically viable business. Returning to the EU’s subsidising of animal farming, a similar situation can be found here in the UK, where around 90% of livestock farmers’ annual profit comes from subsidies, with some farmers making just £12,000, despite being given £44,000 in subsidies. In comparison, only 10% of fruit farmers’ annual profit comes from subsidies. When it comes to dairy, ‘British dairy farmers received over £56 million annually in direct Government payments over recent years, making up nearly 40% of their profits.’

Governments are being lobbied by animal agriculture

Supporting an industry to such an extent that is both damaging to our environment and has connections to multiple human health problems seems bizarre, yet truly demonstrates how the consumption of animal products is considered such a necessity that the government props up what is, effectively, a failing business model.

In 2022 The Vegan Society expressed disappointment at the UK government’s Food Strategy Policy Paper, accusing ministers of ignoring recommendations from their own experts in setting targets for the reduction of meat and dairy consumption. If governments actually took a step back and considered what was in the best interests of people and the planet, they might reconsider where they direct their funding. An oft-mentioned barrier to veganism is cost, yet the level of subsidisation of animal products perhaps unveils how these items are made available to consumers at such low prices. If more subsidies were offered to farmers growing fruits, vegetables and wholefoods, we may see a fairer playing field open up for food producers.

2025 was the warmest June on record across Western Europe. One study estimates that the latest heatwave was responsible for 1,500 deaths across the continent that wouldn’t have occurred without human-induced climate change. And the droughts, wildfires and even flash-flooding that occur as a result of extreme weather, affect wildlife too. In heatwaves, many free-living animals die when they can’t find water and food chains are disrupted, and they’re vulnerable when habitats are destroyed by water or fire.

Being vegan is the best way to save the planet

Choosing a plant-based diet is not only the compassionate choice for animals who are farmed, but also the only choice that makes sense for environmentalists, or simply those who care about the future of their children. We need to radically re-think our food production, and create a system that’s better for animals, better for farmers, and better for our planet. Governments need to stand up against damaging industries and implement policies that benefit more than corporate greed.

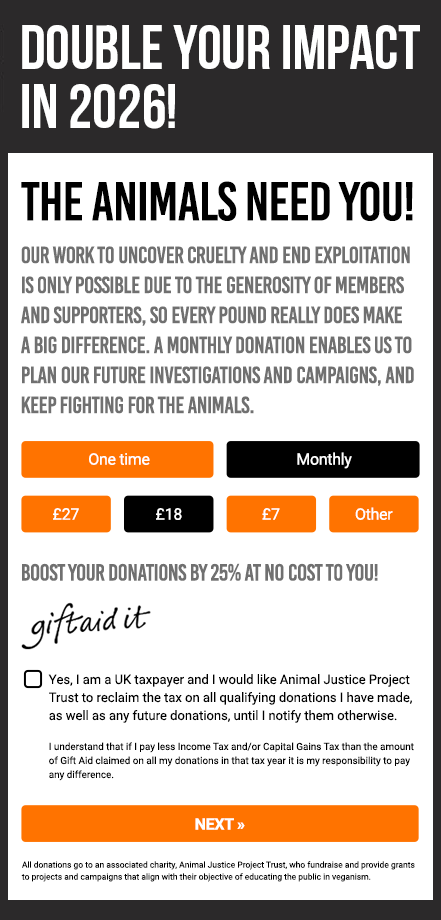

In our ‘Farming for a Future’ campaign, we look towards a world where plant-based is the norm and the positive impact it brings. We look at initiatives that help farmers make the transition away from farming animals and at the success stories that are leading the way.

As always,

For the animals.

.png)

.png)

.webp)

.png)